Blog 7: Sylvia Pankhurst. From Artists to Anti-Fascist, edited by Ian Bullock and Richard Pankhurst,1992.

Posted on

I've already featured each of the books I've written or been associated with in earlier blogs. Now I want to focus on what I believe to be the most significant points in each, I'm beginning with

Sylvia Pankhurst. From Artists to Anti-Fascist, edited by Ian Bullock and Richard Pankhurst,1992.

I've already explained how this book came about and the valuable contributions of all the other authors. (See Blog 1) This time I want to pick out what I think are the most important aspects of my own piece -'Sylvia Pankhurst and the Russian Revolution: the making of a 'Left-Wing' Communist'.

My main sources for it were Pankhurst's own paper the Woman's – later Workers' – Dreadnought and the E Syliva Pankhurst Papers at the International Institute of Social History which I had spent a week reading in Amsterdam

One of my sub-headings is 'The “Invisible” Bolsheviks'. As I would show again much later in Romancing the Revolution, little was known in Britain – or elsewhere, including in Russia itself - about Lenin and the Bolsheviks before the end of 1917. I argue that the result was that ''those who supported the Bolshevik cause from afar had to construct their ideas of Bolshevik actions and policies on the basis of inference. Assumptions based on their own experience, guesswork and wishful thinking played a decisive part' (p 128)

Another section of my contribution is subtitled 'Direct Democracy'. In Pankhurst's case her abiding commitment was to whatever seemed the most radical and genuinely inclusive and participatory form of democracy. I show how – even in March 1918 after the Constituent Assembly in Russia had been forcibly dissolved, with her rather hesitant support. she was still criticising the failure of the Labour Party to include the initiative, referendum and recall in its Labour and the New Socialist Order manifesto. Demands for direct democracy going back to the earliest days of the SDF had featured prominently in the more radical sections of the pre-1917 the British Left .

Pankhurst became convinced after the Russian Revolution had broken out in February/March 1917 that the most democratic form was the workers' soviets though her insistence that 'Housewives' should be included indicates that her conception of soviets was not confined to industrial workers. This led her participation in the Leeds Convention and the 'Workers' and Soldiers' Council of Great Britain' in 1917, her founding her own version of the Communist Party in 1919, being a main target of Lenin's famous 'Left-Wing' Communism. An Infantile Disorder (1920) being expelled from the 'orthodox' British Communist Party in 1921, aligning herself with the Left-Communism of the original Fourth International -and eventually accusing Lenin of 'hauling down the flag of Communism' towards the end of 1922

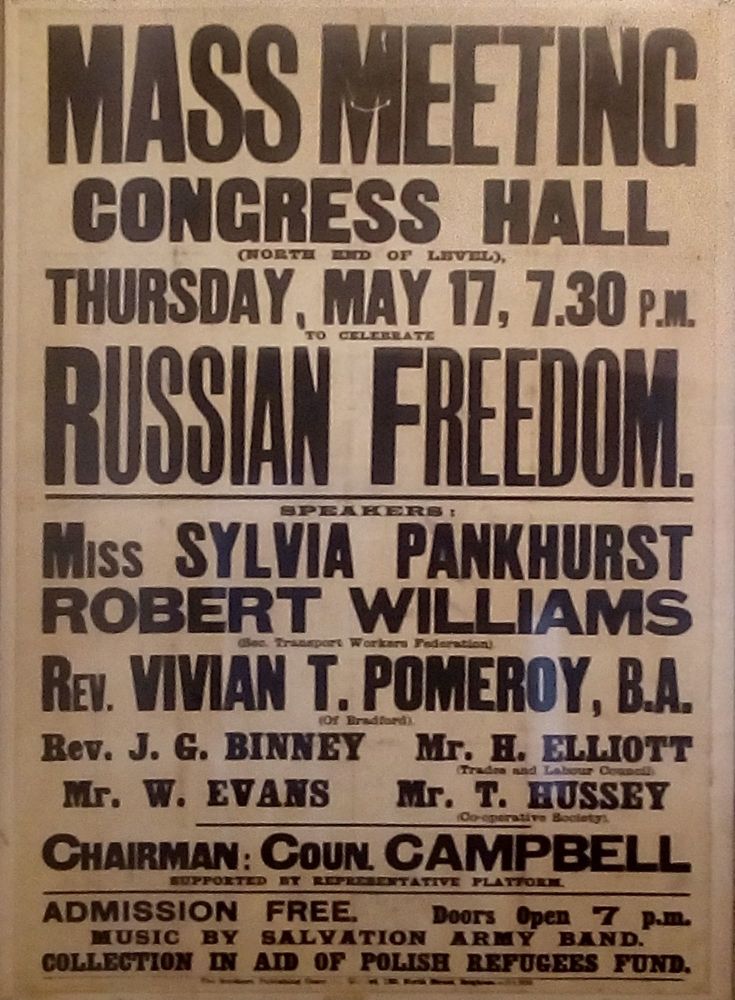

Left-Communism would soon become very much the pursuit of a tiny minority (but see Mark Shilpley's 1988 book Anti-Parliamentary Communism. The Movement for Workers' Councils, 1917-45). I did manage to get in a mention in my piece of the 'Mass Meeting to Celebrate Russian Freedom' held in Brighton on 17th May 1917 at which Sylvia Pankhurst was the main speaker. Much later my (now, sadly, late) friend Andy Durr would give me a poster advertising the meeting. It still hangs on our stairs.

Ian Bullock